Judo vs Jiu Jitsu: The Complete Guide

#Judo #Brazilian Jiu Jitsu #BJJ #Martial Arts #Grappling

Two martial arts. One family tree.

TL;DR

- Judo focuses on standing throws; BJJ focuses on ground fighting and submissions

- Same origin: BJJ descended from judo via Mitsuyo Maeda in Brazil (1914)

- Black belt timeline: Judo 5-7 years, BJJ 8-12 years

- Self-defense: Judo excels standing, BJJ excels on the ground

- Best approach: Many serious grapplers train both

If you’ve ever wondered about the difference between judo and jiu jitsu, you’re asking a question with a fascinating answer. These two grappling arts share far more than most people realize—Brazilian Jiu Jitsu literally descended from judo, carried across the world by a single man over a century ago. The International Judo Federation and International Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu Federation now govern these arts separately, but their shared DNA is undeniable.

But today, they’ve evolved into distinct disciplines with different focuses, rules, and cultures. Judo emphasizes explosive standing throws. BJJ specializes in methodical ground fighting and submissions. Understanding their connection—and their differences—helps you appreciate both arts and choose the right path for your training.

Quick Answer: Judo focuses on standing throws and takedowns, while Brazilian Jiu Jitsu (BJJ) emphasizes ground fighting and submissions. BJJ descended directly from judo when Mitsuyo Maeda brought it to Brazil in 1914. Choose judo for explosive throws; choose BJJ for methodical ground control. Many serious grapplers train both.

What Is the Difference Between Judo and Jiu Jitsu?

The main difference is focus: judo emphasizes standing throws, while BJJ emphasizes ground fighting. Judo aims to throw opponents forcefully onto their backs. BJJ aims to control opponents on the ground and submit them with chokes or joint locks. Both arts share the same origin—BJJ descended from judo in 1914—but evolved in opposite directions over the past century.

Is Judo and Jiu Jitsu the Same?

No. While BJJ descended directly from judo, they’re now distinct martial arts. Judo became an Olympic sport focused on spectacular throws with limited ground time (15-20 seconds before stand-up). BJJ developed extensive ground fighting systems with no time limits on the ground. A judoka and BJJ player train very differently today.

Is Judo Good for Self Defense?

Yes. Judo is excellent for self-defense because most confrontations start standing—exactly where judo excels. A single judo throw onto concrete can end a fight immediately. Judo’s grip fighting also provides distance control against attackers. The main limitation: if you end up on the ground without having thrown your opponent, your toolkit is smaller than a BJJ player’s.

Is Judo Better Than BJJ?

Neither is “better”—they excel in different ranges. Judo is better for standing grappling and throws. BJJ is better for ground fighting and submissions. For complete self-defense, many practitioners train both. MMA fighters cross-train judo for takedowns and BJJ for ground control. The best choice depends on your goals, age, and what type of training appeals to you.

How Long Does It Take to Get a Black Belt in Judo?

Typically 5-7 years of consistent training. Judo’s path to black belt is generally faster than BJJ (8-12 years) because judo has been systematized longer with clearer promotion standards. However, judo’s physical demands—being thrown repeatedly—make the early learning curve steeper than BJJ.

In this guide, we’ll cover:

- The shared history of judo and BJJ (including details most articles miss)

- How Mitsuyo Maeda’s journey from Japan to Brazil created a new martial art

- Technical differences in techniques, training, and competition

- Self-defense applications of each art

- How to decide which is right for you

Let’s start at the beginning.

Part 1: The History

From Feudal Battlefields to the Modern Mat

Before judo existed, there was jujutsu.

For centuries, Japanese samurai developed unarmed combat techniques for situations where they were disarmed or in close quarters. These techniques—throws, joint locks, chokes, and strikes—became known as jujutsu, often translated as “the gentle art” or “the art of yielding.”

By the late 1800s, hundreds of jujutsu schools operated across Japan, each with their own techniques and training methods. But there was a problem: many of these schools used dangerous training methods, and there was no standardized way to practice safely or test techniques against resisting opponents.

Enter Jigoro Kano.

Jigoro Kano Creates Judo (1882)

Born in 1860, Kano was small and frequently bullied as a child. He turned to jujutsu for self-defense, studying under multiple masters and absorbing techniques from various schools.

At just 22 years old, Kano did something revolutionary. He founded the Kodokan and created a new art he called “judo.”

What made judo different?

Kano’s key innovations:

- Removed the most dangerous techniques so students could spar at full intensity without serious injury

- Introduced randori (free practice)—live sparring against resisting opponents

- Created the belt ranking system that martial arts worldwide would later adopt

- Established core philosophies: “Maximum efficiency, minimum effort” (seiryoku zenyo) and “Mutual welfare and benefit” (jita kyoei)

Kano deliberately chose the name “judo” (the gentle way) over “jujutsu” (the gentle art) to distinguish his modern, safer approach from the older, more dangerous schools. The suffix “-do” implies a philosophical path, while “-jutsu” suggests pure technique.

Within years, Kodokan judo proved its effectiveness. In an 1886 tournament organized by the Tokyo Police, Kano’s students dominated representatives from traditional jujutsu schools. Judo was soon adopted into Japan’s school system and began spreading internationally through Kano’s students.

Early Kodokan Judo: More Ground Fighting Than You Think

Here’s something most articles get wrong—or skip entirely.

Early Kodokan judo included extensive ground fighting.

Modern Olympic judo limits ground time to roughly 15-20 seconds before the referee stands fighters up. Watch a judo match today and you’ll see mostly standing throws, with brief ground exchanges.

But Kano’s original vision was different. Early Kodokan training dedicated roughly half its time to newaza—ground techniques including pins, chokes, arm locks, and even leg locks. Kano believed in complete grappling, on the feet and on the ground.

This became even more pronounced after an incident in the 1890s. Mataemon Tanabe, a specialist in ground fighting from the Fusen-ryu school, challenged Kodokan students—and defeated several of them by pulling guard and submitting them on the ground.

Rather than dismiss ground fighting, Kano integrated even more newaza into the Kodokan curriculum. By the early 1900s, many Kodokan judoka were formidable ground fighters.

This matters because one of those ground fighting specialists would carry judo to the other side of the world—and plant the seeds of Brazilian Jiu Jitsu.

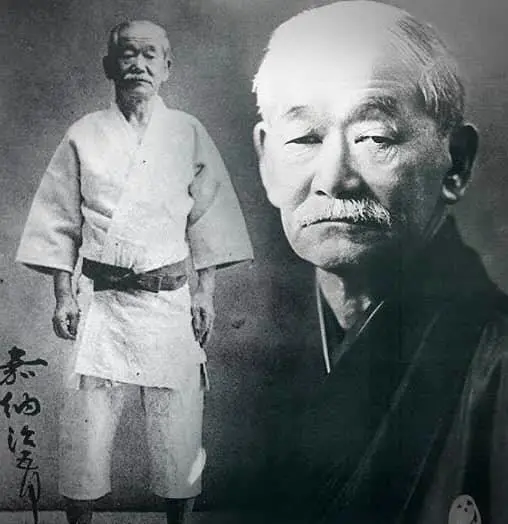

Mitsuyo Maeda: The Journey From Japan to Brazil

Mitsuyo Maeda was born in 1878 and entered the Kodokan in 1897. He became one of Kano’s top students, known particularly for his newaza—his ground fighting.

In 1904, Kano sent Maeda abroad to demonstrate judo’s effectiveness to the world. What followed was one of the most remarkable journeys in martial arts history.

Maeda’s world tour (1904-1914):

- United States (1904): Arrived in New York, gave demonstrations and took challenge matches

- United Kingdom & Scotland: Fought catch wrestlers and learned from their techniques

- Belgium & Spain: Professional fights building his reputation

- Cuba & Mexico: Vale tudo style matches, anything goes

- Central America: Continued the fighting circuit

Maeda wasn’t just demonstrating. He was fighting. Against wrestlers, boxers, and martial artists of every style. By all accounts, he compiled a record of over 1,000 fights without a loss, earning the nickname “Conde Koma”—Count of Combat.

This constant real-world testing shaped what Maeda taught. His style remained grounded in Kodokan judo, but adapted through years of fighting catch wrestlers in the UK and brawlers throughout the Americas.

In 1914, Maeda arrived in Belém, in northern Brazil.

He settled there to help establish the Japanese immigrant community. A local businessman and politician named Gastão Gracie used his connections to assist Maeda with immigration matters.

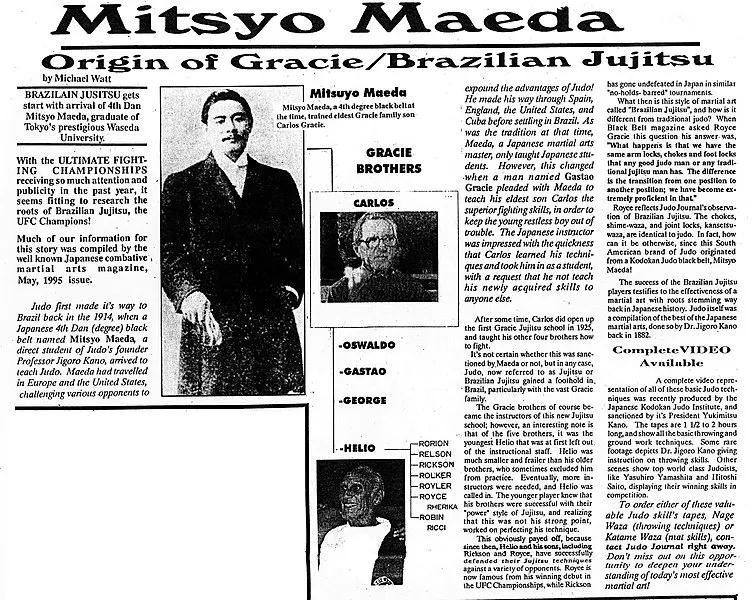

In gratitude, Maeda offered to teach Gastão’s son, Carlos.

What Did Maeda Actually Teach?

This question has sparked decades of debate. But the evidence points clearly in one direction.

Maeda called what he taught “jiu jitsu,” not “judo.” Why?

Several reasons. “Jiu jitsu” was the more recognized term internationally—Kano’s rebranding to “judo” hadn’t fully taken hold abroad. Maeda may also have wanted some distance from Kodokan politics after years of professional fighting (which Kano officially discouraged).

But whatever he called it, what Maeda taught was old-school Kodokan judo—the complete system with heavy emphasis on ground fighting. This was the judo of the early 1900s, not the stand-up-focused Olympic sport it would later become.

His curriculum included:

- Throws and what to do after the throw lands

- Extensive ground work—pins, chokes, arm locks

- Real fighting tested techniques, not sport-optimized ones

This is the DNA of Brazilian Jiu Jitsu.

The Gracie Family Transforms the Art

Carlos Gracie began training with Maeda around 1917. He opened the first Gracie academy in Rio de Janeiro in 1925 and taught his younger brothers—including Hélio.

Hélio Gracie would become the most important figure in BJJ’s evolution. (For more on his philosophy, see our Hélio Gracie quotes collection.)

Born in 1913, Hélio was smaller and weaker than his brothers. Many of the judo throws Carlos learned from Maeda required strength and explosiveness that Hélio simply didn’t have.

So Hélio adapted.

He refined the techniques to rely on leverage rather than strength. He emphasized the ground fighting where a smaller person could control and submit a larger opponent. He developed the guard position—fighting effectively from your back—to a level judo had never reached.

What emerged was something distinct: Gracie Jiu Jitsu, which would later become known as Brazilian Jiu Jitsu.

The Gracies tested their art relentlessly through the “Gracie Challenge”—open invitations to fighters of any style, in vale tudo (anything goes) matches. For decades, they built a reputation in Brazil as unbeatable fighters.

BJJ Goes Global

In 1978, Hélio’s son Rorion moved to Southern California. He taught jiu jitsu out of his garage, slowly building a following.

Then Rorion did something that changed martial arts forever.

In 1993, he co-founded the Ultimate Fighting Championship—a tournament pitting martial artists of different styles against each other with minimal rules. Rorion’s brother Royce, a relatively small man at 175 pounds, entered the tournament.

Royce won UFC 1. Then UFC 2. Then UFC 4.

He defeated boxers, wrestlers, kickboxers, and karate practitioners—many significantly larger than him—by taking them to the ground and submitting them. Suddenly, the world saw what the Gracies had known for decades: ground fighting works.

Brazilian Jiu Jitsu exploded globally. Today it’s one of the fastest-growing martial arts in the world.

The Irony of Modern Judo

Meanwhile, judo went in a different direction.

Kano achieved his dream of Olympic inclusion posthumously—judo debuted at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. But Olympic status came with trade-offs.

To make judo more spectator-friendly, rules evolved to emphasize dramatic throws. Ground time was progressively limited. In 2010, the IJF controversially banned leg grabs entirely, removing techniques like the single-leg and double-leg takedowns that were once part of judo’s arsenal.

The irony: BJJ may now be closer to Kano’s original complete judo than modern Olympic judo is.

Early Kodokan judoka spent half their training on the ground. They used leg grabs and trained submissions extensively. Maeda carried that complete system to Brazil, where the Gracies preserved and expanded the ground fighting while Olympic judo was streamlining it away.

Two arts, one origin—but they evolved in opposite directions.

Timeline: The Judo to BJJ Family Tree

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1882 | Jigoro Kano founds Kodokan Judo in Tokyo |

| 1897 | Mitsuyo Maeda enters the Kodokan |

| 1904 | Maeda begins world tour, demonstrating and fighting |

| 1914 | Maeda arrives in Brazil, settles in Belém |

| ~1917 | Carlos Gracie begins training with Maeda |

| 1925 | First Gracie Jiu Jitsu academy opens in Rio |

| 1964 | Judo debuts at Tokyo Olympics |

| 1978 | Rorion Gracie moves to California |

| 1993 | UFC 1—Royce Gracie proves BJJ’s effectiveness |

| 2002 | ADCC establishes premier no-gi grappling championship |

Part 2: Techniques and Training

With the history established, let’s examine how these arts differ in practice today.

Standing Techniques

Judo’s bread and butter:

Judo is built around the throw. The goal is to take your opponent from standing to their back with force and control. A perfect throw—ippon—wins the match instantly.

Judo throws fall into several categories:

- Hip throws (koshi-waza): Using your hip as a fulcrum to rotate your opponent over your body. Classic examples: O-goshi, Harai-goshi.

- Hand throws (te-waza): Using arm and shoulder mechanics. Classic examples: Seoi-nage (shoulder throw), Tai-otoshi.

- Foot sweeps (ashi-waza): Timing your opponent’s weight shift to sweep their legs. Classic examples: De-ashi-barai, O-soto-gari.

- Sacrifice throws (sutemi-waza): Throwing yourself to throw your opponent. Classic example: Tomoe-nage (stomach throw).

Judo’s throwing curriculum is vast and sophisticated, developed over 140 years.

BJJ’s standing game:

BJJ players need to get the fight to the ground, but they typically spend less time on takedown development than judoka. Common approaches include:

- Wrestling takedowns (single-leg, double-leg)

- Simplified judo throws

- Guard pulling—sitting down and initiating from the guard

Guard pulling is controversial. Critics argue it’s “giving up” the standing phase. Advocates note that in sport BJJ, pulling guard is often the highest-percentage path to your best game. In self-defense, though, you’d never want to sit down voluntarily.

Ground Techniques

This is where the arts diverge most dramatically.

Judo’s ground game:

Judo includes legitimate ground fighting—pins (osaekomi), chokes (shime-waza), and arm locks (kansetsu-waza). A judoka can win by pinning their opponent for 20 seconds, or by submission.

But there’s a catch: limited ground time.

If fighters aren’t actively progressing on the ground, the referee stands them back up—usually within 15-20 seconds. This means judo ground fighting is about rapid transitions and immediate attacks, not patient position advancement.

BJJ’s ground game:

BJJ is built for the ground. There are no stand-ups for inactivity. Matches can spend their entire duration in ground fighting.

This created space for extraordinary depth:

Guard positions: BJJ developed the guard—fighting from your back—into dozens of distinct positions:

- Closed guard (legs wrapped around opponent)

- Open guard (various leg configurations)

- Half guard (one leg controlled)

- Spider guard, De La Riva guard, Butterfly guard, and many more

Guard passing: Equally complex systems for getting past your opponent’s legs to dominant positions.

Submissions: BJJ’s submission catalog is extensive:

- Chokes: Rear naked choke, guillotine, triangle, D’arce, anaconda

- Arm locks: Armbar, kimura, americana, omoplata

- Leg locks: Heel hook, kneebar, toe hold, calf slicer

Sweeps: Techniques to reverse position from bottom to top.

Back control: Taking your opponent’s back and attacking the neck.

BJJ’s ground game has had 100 years to develop since Hélio began adapting techniques, with acceleration after UFC 1 brought global attention and thousands of practitioners worldwide began innovating.

The Guard: BJJ’s Greatest Innovation

If there’s one technique that defines BJJ’s divergence from judo, it’s the guard.

In most martial arts, being on your back means you’re losing. In BJJ, a skilled guard player is dangerous from bottom position.

Hélio Gracie developed the guard because he needed to. Smaller and weaker than his brothers and opponents, he couldn’t always take people down or stay on top. From his back, though, he could use his legs to control distance, set up sweeps, and attack with chokes and joint locks.

Today’s guard systems have evolved far beyond anything Hélio could have imagined. Elite competitors like Keenan Cornelius, Mikey Musumeci, and Gordon Ryan have innovated constantly, creating new positions and attacks.

The guard changed martial arts forever. It proved that being on your back isn’t automatically a losing position—it’s just another position to fight from.

Training Methods Compared

How you spend your time in class differs significantly between the two arts.

A typical judo class:

- Warm-up and ukemi (breakfalls) – Learning to fall safely is fundamental; you can’t train throws without it

- Uchi-komi – Repetitive throw entries, drilling the movement pattern

- Nage-komi – Actually completing throws on a partner

- Randori – Free sparring, attempting throws on a resisting opponent

- Newaza – Ground sparring (often a smaller portion of class)

Judo training is physically demanding from day one. You’re being thrown, learning to fall, engaging in gripping battles that tax your forearms. The learning curve is steep.

A typical BJJ class:

- Warm-up – Often movement-based drills

- Technique instruction – Professor demonstrates position, sweep, or submission

- Drilling – Partners practice the technique cooperatively

- Positional sparring – Specific scenarios (e.g., start in guard, try to sweep/pass)

- Open rolling – Free sparring from knees or standing

BJJ’s entry is often gentler. You can “survive” early by playing defense. Tapping early prevents injury. Intensity scales with experience and goals.

Both arts emphasize live sparring as essential to development. You can’t learn judo without randori, and you can’t learn BJJ without rolling.

The Gi Question

Both arts traditionally train in a gi (uniform), but the relationship with the gi differs.

Judo gi:

- Thick, heavy weave designed for gripping and throwing

- Reinforced collar and lapels

- Traditionally white or blue only

- Required for virtually all judo training and competition

BJJ gi:

- Lighter, closer-fitting

- Multiple weave options (gold, pearl, ripstop)

- Many colors and designs permitted

- Gi and no-gi are distinct disciplines

No-gi grappling:

This is where judo and BJJ really diverge. Judo rarely trains without the gi. BJJ has a massive no-gi scene that’s growing faster than gi BJJ.

No-gi changes everything:

- No collar chokes, no lapel grips

- Different grip fighting (overhooks, underhooks, wrist control)

- Leg locks become more prominent

- Generally faster pace

If you want to compete in MMA, no-gi skills are essential. And right now, BJJ is where no-gi grappling lives.

Part 3: Competition

Judo Competition

Judo matches are fast. Senior matches last 4 minutes. The goal: throw your opponent flat on their back with force and control.

Ways to win:

- Ippon (full point) – A clean throw to the back, a 20-second pin, or a submission. Ends the match immediately.

- Two waza-ari – Two half-point throws equal ippon.

- Most points at time – If no ippon, highest score wins.

The limited ground rule:

This is crucial. If fighters go to the ground, they must show “progress”—active attacks toward pin or submission. Otherwise, the referee calls “matte” and stands them up. Ground time rarely exceeds 15-20 seconds.

This rule shapes judo’s entire approach to ground fighting: immediate, explosive attacks rather than patient position building.

Golden score:

If the match is tied at regulation, it goes to golden score overtime. First to score any point wins. Matches can extend significantly.

BJJ Competition

BJJ matches are longer. Depending on belt level and division, matches run 5-10 minutes. The goal: submit your opponent or accumulate the most points through positional advancement.

Points (IBJJF rules):

- Takedown: 2 points

- Sweep: 2 points

- Knee on belly: 2 points

- Guard pass: 3 points

- Mount: 4 points

- Back control with hooks: 4 points

Advantages: Near-submissions, near-sweeps, and near-passes earn advantages, which serve as tiebreakers.

Ways to win:

- Submission (immediate victory)

- Most points at time

- Most advantages if points tied

No stand-ups:

Unlike judo, BJJ referees don’t stand fighters up for inactivity on the ground. If both fighters are content to stall, that’s on them—but the audience and points system encourage action.

Other formats:

BJJ has multiple rule sets:

- ADCC: No-gi, submission-only for first half of match, then points

- EBI: Submission-only with overtime escape rounds

- Various sub-only formats: No points, submission wins or draw

This variety reflects BJJ’s ongoing evolution and debates about what the sport should emphasize.

Competitive Pathways

Judo:

- Local → Regional → National → International

- IJF World Tour (Grand Slams, Grand Prix, Masters)

- Olympic Games – The pinnacle

- World Championships

Judo’s Olympic status brings significant funding, visibility, and structure. It’s one of the most practiced martial arts globally, largely due to Olympic inclusion.

BJJ:

- Local → Regional → Major championships

- IBJJF World Championship (“Mundials”)

- Pan Americans, Europeans

- ADCC Submission Wrestling World Championships

- Various professional leagues

BJJ is not in the Olympics—yet. There are ongoing efforts for 2028 inclusion, but nothing confirmed. For now, the Mundials and ADCC remain the sport’s most prestigious titles.

Part 4: Self-Defense

Both arts work for self-defense. They work in different ranges.

Judo for Self-Defense

Strengths:

Most fights start standing. Judo’s entire focus is controlling the standing phase and putting your opponent on the ground—hard.

A single throw onto concrete can end a confrontation immediately. The same O-soto-gari that scores waza-ari on a judo mat is devastating on pavement.

Judo’s grip fighting provides distance control. You can manage space, break grips, and prevent an attacker from striking effectively.

The art works against larger opponents. Leverage and timing allow smaller judoka to throw bigger people. Kano designed it this way intentionally.

Limitations:

If you end up on the ground without having thrown your opponent, your toolkit is smaller than a BJJ player’s. Judo ground work exists, but it’s trained less extensively.

Judo requires gripping. Against an attacker in a t-shirt, your jacket grips may tear the shirt rather than control the body.

Modern sport judo has removed some practical techniques. Leg grabs, while effective in self-defense, are no longer part of competition judo.

BJJ for Self-Defense

Strengths:

If the fight goes to the ground—and many do—BJJ is unmatched. You can control an attacker without striking, which has legal benefits in aftermath situations.

BJJ submissions end fights definitively. A choke or joint lock doesn’t require repeated strikes; it incapacitates.

The art is effective from disadvantaged positions. If you’re mounted or pinned, BJJ gives you tools to escape and reverse. Other arts simply don’t address this range.

Hélio specifically designed his approach for the smaller defender against the larger attacker. The art’s DNA includes leverage over strength.

Limitations:

The ground is dangerous in real confrontations. Concrete hurts. Multiple attackers can kick you. Weapons can appear.

Getting the fight to the ground isn’t always easy. Sport BJJ’s guard pulling works in competition but is poor strategy in a real fight.

There’s a gap between sport BJJ and self-defense BJJ. Some modern sport techniques—like sitting guard games—have limited real-world application.

The Honest Assessment

Both work. Neither is complete alone.

For comprehensive self-defense grappling, you want:

- Judo (or wrestling) for the clinch and takedown

- BJJ for ground control and submissions

- Awareness of striking, even if you’re primarily a grappler

This is why MMA fighters cross-train. And why serious self-defense practitioners often study multiple arts.

Part 5: Choosing Your Path

Which Is Harder to Learn?

This depends on what you mean by “hard.”

Judo’s learning curve:

Judo starts steep. Before you can even be thrown safely, you must learn ukemi—breakfalls. Then you’re thrown repeatedly while internalizing the patterns.

Throws are timing-dependent. You might understand a technique intellectually but lack the timing to execute it for months or years. Randori against a good judoka as a beginner is humbling.

The physicality starts on day one. Gripping battles exhaust your forearms. Falls accumulate impact.

BJJ’s learning curve:

BJJ often starts gentler. You can “survive” early by learning defensive posture and tapping before joints lock. The pace is often more controlled.

Positional sparring lets you work specific scenarios before open rolling. Intensity can ramp up gradually.

That said, BJJ’s depth is immense. Blue belt (typically 1-2 years) represents fundamental competence. Black belt typically takes 8-12 years—longer than judo’s 5-7 year average.

Mastery in either art requires a lifetime.

Physical Considerations

Age:

Judo’s impact is harder on older bodies. You’re being thrown, you’re falling, and this compounds over time. Many lifelong judoka transition to BJJ in their 40s and 50s.

BJJ is more accessible for older beginners. You can modulate intensity, and many schools have masters divisions and “old man jiu jitsu” approaches.

That said, some judoka train safely into their 60s and beyond. And BJJ accumulates its own joint stress over years.

Body type:

Both arts accommodate all body types, but different builds find different techniques natural.

In judo, lower center of gravity helps with certain throws. Grip strength matters significantly.

In BJJ, long limbs help with triangles and guard control. Flexibility aids various guard games. But every body type can find their game—BJJ is notable for how different practitioners develop completely different styles.

Injury risk:

Judo has higher acute injury risk from throws—shoulder injuries, concussions from falls, impact-related trauma.

BJJ has significant joint injury risk, particularly shoulders, elbows, and knees. Neck issues are common. The injury rate per training hour may be lower than judo, but high training volume adds up.

Neither art is “safe.” Both require intelligent training, good partners, and willingness to tap or fall correctly.

Decision Framework

Choose judo if:

- Explosive, dynamic action appeals to you

- You prefer standing combat

- Olympic aspirations matter

- Learning to fall safely interests you

- Your body handles impact well

- You want something with traditional Japanese roots

Choose BJJ if:

- Ground fighting interests you

- You want a chess-like, strategic art

- You’re starting later in life

- Competing without Olympic requirements is fine

- You want both gi and no-gi options

- MMA is a goal

Choose both if:

- You want complete grappling skills

- Your schedule allows training both

- You’re serious about self-defense

- MMA is the goal

Finding Schools

What to look for (either art):

- Instructor with verifiable credentials (judo rank should be traceable; BJJ lineage matters)

- Regular live sparring (randori/rolling)

- Clean, safe facilities

- Positive training culture

- Competition opportunities if you want them

Red flags:

- Instructor gets defensive about credentials

- No live sparring (“too deadly to spar”)

- Excessive contracts and fees

- Cultish dynamics

- Unwillingness to let you watch a class first

Part 6: The Modern Landscape

The Cross-Training Revolution

Today’s elite grapplers rarely train just one art.

MMA proved that specialists get exposed. A pure boxer gets taken down. A pure BJJ player gets knocked out standing. A pure judoka gets leg-locked on the ground.

Complete grapplers now combine:

- Judo for throws and clinch control

- BJJ for guard and submissions

- Wrestling for takedowns and top pressure

This cross-training flows both ways. BJJ players increasingly seek judo instruction for their standup. Judoka train BJJ to round out their ground games.

Some notable cross-trainers:

| Athlete | Background | Achievement |

|---|---|---|

| Ronda Rousey | Olympic Judo Bronze | UFC Bantamweight Champion |

| Travis Stevens | Olympic Judo Silver | BJJ Black Belt, teaches both |

| Karo Parisyan | Judo Black Belt | UFC veteran, famous for judo in MMA |

| Fabricio Werdum | BJJ World Champion | UFC Heavyweight Champion |

| Satoshi Ishii | Olympic Judo Gold | Transitioned to MMA/BJJ |

The lines between grappling arts are blurring. And both judo and BJJ benefit from the exchange.

The Future of Both Arts

Judo’s challenges:

The IJF’s rule changes—particularly the leg grab ban—frustrate traditionalists who believe judo has moved too far from Kano’s complete vision. Some countries report declining participation, with students choosing BJJ or MMA instead.

Judo’s strengths:

Olympic status brings funding, media exposure, and structural support that BJJ can’t match. The art has deep traditions and strong international federation. School physical education programs in many countries include judo.

BJJ’s growth:

BJJ is arguably the fastest-growing martial art globally. FloGrappling and other media have created stars. Professional leagues are expanding. Innovation continues at remarkable pace.

BJJ’s challenges:

The sport lacks unified governance. Multiple competing organizations (IBJJF, ADCC, various professional leagues) create fragmentation. No Olympic path exists yet. Concerns about “belt mills” and credential verification persist.

Both arts will continue evolving. The question isn’t which will survive—both will—but how they’ll change.

Conclusion: Different Branches, Same Tree

Judo and Brazilian Jiu Jitsu are family.

They share the same origin: Jigoro Kano’s Kodokan, founded in Tokyo in 1882. They share the same transmission vector: Mitsuyo Maeda, who carried old-school Kodokan judo across the world and taught it to Carlos Gracie in Brazil. They share the same fundamental insight: that leverage and technique can defeat strength and size.

But they’ve grown in different directions.

Judo became an Olympic sport, spectator-friendly, with explosive throws and limited ground time. BJJ stayed in the gyms and backyards of Brazil before exploding globally after UFC 1, developing the most sophisticated ground fighting system in martial arts history.

Neither is “better.” They’re different tools for different ranges.

If you want to throw someone spectacularly, train judo. If you want to control someone methodically on the ground, train BJJ. If you want complete grappling, train both.

The path you choose matters less than the commitment you bring. Both arts will challenge you, humble you, and ultimately transform you—just as they’ve transformed millions of practitioners since Kano first gathered students in a 12-mat room in 1882.

Train hard. Tap early. Respect the art.

Running a judo club or BJJ academy? MartialArts.io helps you track student progress through belt ranks, manage attendance, and grow your school.

© 2025 MartialArts.io. All rights reserved.